What if your digestive system held the key to understanding anxiety depression, and even memory problems? This isn’t science fiction.

Recent discoveries reveal that your gut and brain communicate constantly through complex biological pathways.

Scientists now recognize that mental health and digestive wellness are deeply intertwined.

Your intestinal tract contains millions of nerve cells. These cells form a sophisticated network that sends signals directly to your brain. Gut brain axis research has uncovered that this communication flows both ways affecting everything from mood to decision making.

Medical professionals are rethinking traditional treatment approaches. They now understand that nutrition for brain health starts in your digestive tract. The foods you eat influence the billions of microorganisms living in your gut which in turn affect your emotional state and cognitive abilities.

This paradigm shift challenges outdated medical models. Healthcare providers increasingly recognize that treating mental health requires addressing digestive wellness, and vice versa.

Key Takeaways

- Your gut contains a complex nervous system that directly communicates with your brain through neural hormonal, and immune pathways

- Mental health conditions like anxiety and depression are significantly influenced by digestive system health

- Dietary choices directly impact the gut microbiome which affects mood cognition, and emotional well being

- Modern medicine now views the gut and brain as interconnected systems rather than separate organs

- Nutrition serves as a powerful tool for modulating brain function through the gut-brain axis

- Effective mental health treatment increasingly requires attention to digestive wellness and nutritional factors

1. Understanding the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

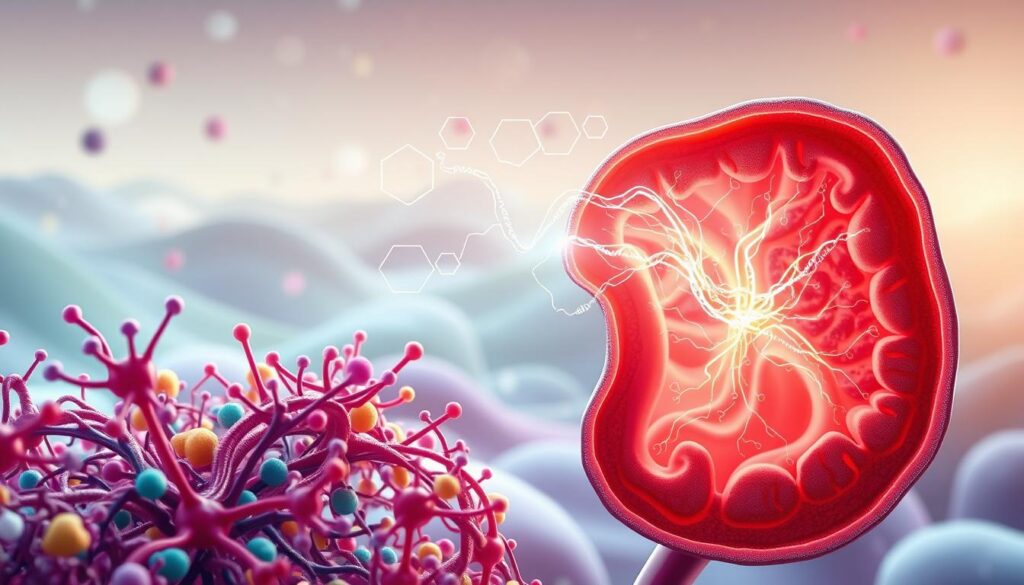

Deep within your digestive system lies a complex ecosystem that actively shapes your thoughts emotions, and mental well-being. This intricate network, known as the microbiota gut brain axis represents a revolutionary discovery in modern medicine.

Scientists now understand that your gut contains trillions of microorganisms that communicate directly with your brain through multiple biological pathways.

The relationship between these intestinal microbes and your central nervous system extends far beyond simple digestion. Research demonstrates that this connection influences cognitive function, emotional regulation, and even personality traits. Understanding how this system operates provides essential insights into maintaining both physical and mental wellness.

1.1 Defining the Gut Brain Connection in Modern Science

The microbiota gut brain axis emerged as a major research focus in the early 2000s when scientists began connecting digestive health with neurological conditions. This biological system encompasses three primary components the gut microbiome the intestinal barrier, and the brain’s neural networks.

Each element plays a crucial role in maintaining overall health.

Your gut microbiome consists of approximately 100 trillion microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes. These tiny organisms outnumber your human cells by a ratio of 10 to 1. The collective genetic material of these microbes contains more than 3 million genes compared to the roughly 20,000 genes in human DNA.

Modern research has transformed medical understanding of this relationship. Previously, doctors viewed the gut and brain as separate systems with minimal interaction. Current evidence reveals they function as integrated partners in regulating everything from immune responses to emotional states.

The gut microbiome and mental health connection operates through sophisticated biochemical signaling. Beneficial bacteria produce compounds that directly affect brain chemistry. These microbial metabolites travel through your bloodstream crossing the blood-brain barrier to influence neurotransmitter production and neural activity.

1.2 The Bidirectional Communication System Explained

The term bidirectional describes how information flows both from brain to gut and from gut to brain simultaneously. When you experience stress or anxiety your brain sends signals that alter digestive function blood flow to the intestines, and gut bacteria composition. This explains why nervous situations often trigger stomach discomfort or changes in appetite.

Communication travels in the opposite direction as well. Your gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters, hormones, and immune signaling molecules that directly influence brain function. These chemical messengers affect mood regulation, cognitive performance, and stress responses. The microbiota gut-brain axis utilizes four primary communication channels to facilitate this constant dialogue.

| Communication Pathway | Primary Mechanism | Key Functions | Impact on Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vagus Nerve | Direct neural signaling between gut and brain stem | Transmits sensory information, regulates inflammation, controls digestive processes | Influences mood, anxiety levels, and gut motility |

| Immune System | Cytokines and inflammatory molecules | Regulates inflammation response, protects gut barrier integrity | Links gut inflammation to depression and cognitive decline |

| Endocrine System | Hormones produced by gut bacteria and intestinal cells | Controls appetite, stress response, circadian rhythms | Affects cortisol levels, metabolism, and emotional stability |

| Metabolic Pathway | Short-chain fatty acids and other bacterial metabolites | Provides energy to gut cells, modulates gene expression | Supports brain health, reduces neuroinflammation |

Each pathway operates continuously, processing millions of signals every day. The vagus nerve serves as the primary information highway containing approximately 80-90% of nerve fibers that carry information from gut to brain. This represents a fundamental shift from traditional understanding which assumed most signals traveled from brain to gut.

Gut bacteria also produce over 30 different neurotransmitters, including serotonin dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid GABA. These chemical messengers play essential roles in regulating mood and cognitive function. The bidirectional nature of this system means that improving gut health can directly enhance mental well-being, while managing stress supports digestive function.

1.3 Why This Connection Matters for Overall Health

The clinical significance of the microbiota-gut-brain axis extends across multiple medical disciplines. Disruptions in this communication network have been linked to conditions ranging from irritable bowel syndrome to major depressive disorder. Understanding these connections opens new possibilities for treatment approaches that address root causes rather than just symptoms.

Research demonstrates strong correlations between gut dysbiosis microbial imbalance and various mental health conditions. Studies show that individuals with depression often display altered gut microbiome composition compared to healthy controls. Similar patterns appear in anxiety disorders autism spectrum disorders, and even Parkinson’s disease.

The gut microbiome and mental health relationship also influences cognitive performance and brain aging. Beneficial gut bacteria produce compounds that protect neurons from damage and support memory formation. Maintaining a diverse, balanced microbiome may reduce the risk of age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases.

Inflammatory bowel conditions demonstrate the practical importance of this axis. Patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis experience depression and anxiety at rates significantly higher than the general population. This association isn’t merely psychological stress from chronic illness the intestinal inflammation directly affects brain chemistry through immune signaling pathways.

Recognizing the microbiota gut-brain axis as a unified system requires integrative treatment strategies. Effective interventions must address both psychological stress management and nutritional support for beneficial gut bacteria. This holistic approach yields better outcomes than treating mental and digestive symptoms as separate issues.

The implications for preventive health care are equally significant. Dietary choices antibiotic use sleep patterns, and stress levels all impact gut microbiome composition. These lifestyle factors subsequently influence mental health immune function, and chronic disease risk. Supporting the gut-brain axis through nutrition and lifestyle modifications represents a powerful strategy for maintaining long-term wellness.

2. The Enteric Nervous System: Your Second Brain

Hidden within the walls of your digestive tract lies a complex network of over 100 million neurons that functions remarkably like a second brain. This sophisticated system operates continuously managing digestive processes with minimal input from your central nervous system.

The enteric nervous system represents one of the most fascinating aspects of human physiology demonstrating that intelligence exists beyond the brain itself.

Scientists have discovered that this gut-based neural network contains more neurons than your spinal cord. It produces and utilizes more than 30 different neurotransmitters many identical to those found in your brain. This remarkable similarity explains why the gut can influence mood, cognition, and emotional well-being in profound ways.

2.1 Anatomy and Function of the Enteric Nervous System

The enteric nervous system stretches throughout your entire gastrointestinal tract, from the esophagus to the anus. This extensive network consists of two primary layers of nerve tissue embedded in the intestinal walls. These layers work together to coordinate digestive functions with precision and efficiency.

The outer layer, called the myenteric plexus, controls the rhythmic contractions that move food through your digestive system. The inner layer, known as the submucosal plexus, regulates enzyme secretion and blood flow to the intestinal lining. Together, these networks manage countless operations every day without conscious effort.

Your gut’s neural network communicates through an impressive array of chemical messengers. The enteric nervous system produces serotonin, dopamine acetylcholine, and numerous other neurotransmitters. In fact, approximately 95% of your body’s serotonin is manufactured in the gut, not the brain.

This neural network also contains various types of specialized cells. Sensory neurons detect chemical and mechanical changes in the gut environment. Motor neurons control muscle contractions and glandular secretions. Interneurons connect these components, creating an integrated communication system that rivals the sophistication of brain circuits.

2.2 Independent Operations of the Gut’s Neural Network

The most remarkable feature of the enteric nervous system is its ability to function autonomously. Your gut can manage digestive processes without receiving instructions from your brain. This independence becomes evident in individuals with spinal cord injuries who maintain normal digestive function despite severed connections to the central nervous system.

Peristalsis, the wave like muscle contractions that propel food through your digestive tract occurs automatically through local neural circuits. The ENS detects when food enters a section of intestine and initiates coordinated contractions to move it forward. This process continues seamlessly even when the vagus nerve connection to the brain is interrupted.

Enzyme secretion represents another autonomous function controlled by gut neurons. When food arrives in different digestive regions, local sensors trigger the release of specific digestive enzymes. The enteric nervous system matches enzyme production to the type and amount of nutrients present, optimizing digestion without brain involvement.

Blood flow regulation in the intestinal walls also operates independently. After eating, the gut’s neural network increases blood supply to digestive organs to support nutrient absorption. This redistribution of blood happens automatically, managed entirely by local neural circuits within the intestinal walls.

| ENS Function | Primary Mechanism | Independence Level | Key Neurotransmitters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peristaltic Movement | Coordinated muscle contractions via myenteric plexus | Fully autonomous | Acetylcholine, Serotonin |

| Enzyme Secretion | Chemical sensing triggers glandular release | Fully autonomous | Vasoactive intestinal peptide |

| Blood Flow Control | Vasodilation and constriction of intestinal vessels | Partially autonomous | Nitric oxide, Substance P |

| Immune Response | Detection of pathogens triggers defensive reactions | Partially autonomous | Multiple neuropeptides |

2.3 The Link Between Gut Feelings and Emotional States

The phrase trust your gut instinct has a solid scientific foundation rooted in the enteric nervous system. Your gut actually sends more signals to your brain than your brain sends to your gut. These ascending messages influence emotions decision-making, and intuitive feelings in ways researchers are only beginning to understand.

When you experience anxiety or stress, your brain sends signals that alter gut function. This communication triggers the familiar sensation of butterflies in your stomach or stress-induced digestive upset. The enteric nervous system responds to emotional states by changing motility, secretion patterns, and sensitivity levels throughout the digestive tract.

The bidirectional nature of this communication means gut disturbances can trigger emotional responses as well. People with irritable bowel syndrome often experience heightened anxiety and depression. Research demonstrates that inflammation or dysfunction in the gut’s neural network can directly influence mood regulation centers in the brain.

Visceral sensations from your gut contribute to emotional awareness and decision-making processes. Studies using brain imaging show that gut signals activate emotional processing regions before conscious awareness occurs. This explains why intuitive feelings often manifest as physical sensations in the abdomen rather than as thoughts.

The enteric nervous system doesn’t seem capable of thought as we know it but it communicates back and forth with our big brain with profound results.

Neuroscientists have identified specific pathways through which gut sensations influence emotional states. The enteric nervous system communicates with brain regions including the amygdala hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. These areas process emotions memories, and executive functions explaining why gut health impacts mental well-being so significantly.

Understanding this connection validates the importance of maintaining gut health for emotional balance. When your digestive system functions optimally communication with your brain remains clear and supportive. Disruptions to the ENS, whether from poor diet, stress, or illness, can create cascading effects on mood and cognitive performance.

The enteric nervous system demonstrates that your gut truly deserves recognition as a second brain. Its complexity, autonomy, and intimate connection with emotional processing reveal that digestive health extends far beyond simple nutrient absorption. This neural network serves as a critical foundation for both physical wellness and mental health.

3. Vagus Nerve Communication The Primary Information Highway

Deep within your body runs a remarkable communication network that links your digestive system directly to your brain through the vagus nerve. This extensive neural pathway serves as the primary conduit for vagus nerve communication transmitting vital information that influences everything from your mood to your immune response.

Understanding how this biological superhighway operates reveals why gut health has such profound effects on mental and physical wellness.

The vagus nerve represents one of the most sophisticated communication systems in the human body. It functions as a two-way street, though the traffic flows predominantly in one direction with surprising implications for how we understand the gut-brain connection.

How the Vagus Nerve Connects Gut and Brain

The vagus nerve originates in the brainstem, specifically in the medulla oblongata, and branches extensively throughout the body. It earns its name from the Latin word vagus meaning wandering because of its remarkable reach to nearly every major organ system. This tenth cranial nerve creates direct physical connections between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract.

The anatomical pathway begins at the brainstem and descends through the neck alongside major blood vessels. From there it branches to innervate the esophagus, stomach small intestine, and portions of the colon. These dense neural connections allow for constant monitoring and regulation of digestive processes.

What makes vagus nerve communication particularly fascinating is its directional bias. Approximately 80 to 90 percent of vagal nerve fibers are afferent meaning they carry information from the gut to the brain rather than the reverse.

This finding fundamentally challenges the traditional view that the brain primarily controls the gut, revealing instead that the gut continuously informs and influences brain function.

The vagus nerve contains different types of nerve fibers that serve distinct functions:

- Sensory fibers detect chemical signals mechanical stretch, and temperature changes in the digestive tract

- Motor fibers control muscle contractions that move food through the digestive system

- Secretory fibers regulate the release of digestive enzymes and stomach acid

- Immunological monitoring fibers detect inflammatory markers and immune system activity

Neural Signals and Their Journey Through the Body

The types of information transmitted through vagus nerve communication are remarkably diverse and complex. These neural signals carry data about the internal state of the digestive system providing the brain with continuous updates about what’s happening in the gut.

Nutrient sensors along the vagal pathway detect the presence of specific macronutrients, including proteins fats, and carbohydrates. When you eat a meal these sensors identify what nutrients are present and signal the brain about nutritional status. This information influences feelings of satiety food cravings, and even mood states.

Mechanical receptors respond to the physical stretching of the stomach and intestinal walls. These signals inform the brain about the volume of food consumed and contribute to the sensation of fullness. The mechanical information also helps coordinate digestive motility and enzyme secretion.

Chemical messengers produced by gut bacteria travel through the vagal pathway as well. The microbiome manufactures numerous compounds including short chain fatty acids neurotransmitter precursors, and signaling molecules. The vagus nerve detects these microbial metabolites and communicates their presence to brain regions involved in emotional regulation.

Inflammatory markers represent another critical category of vagal signals. When the gut barrier becomes compromised or inflammation develops, immune cells release cytokines and other inflammatory molecules. The vagus nerve detects these signals and alerts the brain, triggering responses that can affect mood, cognition, and behavior.

The journey of these neural signals follows a specific route. Information travels from gut sensors through vagal afferent fibers to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the brainstem. From this relay station, signals disperse to multiple brain regions, including:

- The hypothalamus, which regulates appetite, stress response, and hormone production

- The amygdala, which processes emotions and fear responses

- The hippocampus, which handles memory formation and emotional regulation

- The prefrontal cortex, which manages decision-making and executive function

Vagal Tone as a Marker of Mental and Physical Health

Vagal tone refers to the activity level of the vagus nerve and serves as an important biomarker for overall health. This measurement reflects how well the vagus nerve performs its regulatory functions throughout the body. Higher vagal tone indicates better vagus nerve communication and typically correlates with improved health outcomes.

Clinicians measure vagal tone through heart rate variability HRV which examines the variation in time intervals between heartbeats. The vagus nerve influences heart rate through the parasympathetic nervous system so greater variability indicates stronger vagal activity. This measurement provides insights into both mental and physical health status.

High vagal tone is associated with numerous positive health markers. Individuals with robust vagal function typically demonstrate better emotional regulation, experiencing less anxiety and recovering more quickly from stress. They show improved digestive efficiency, with better nutrient absorption and more regular bowel movements.

The anti-inflammatory effects of strong vagal tone are particularly significant. The vagus nerve releases acetylcholine which dampens inflammatory responses throughout the body. This anti-inflammatory action protects against chronic diseases and supports mental health by reducing neuroinflammation.

| Vagal Tone Level | Physical Health Indicators | Mental Health Indicators | Digestive Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Vagal Tone | Lower blood pressure, reduced inflammation, stronger immune response, better cardiovascular health | Greater emotional resilience, improved mood stability, reduced anxiety, better stress recovery | Efficient digestion, regular motility, optimal enzyme secretion, healthy gut barrier |

| Moderate Vagal Tone | Normal blood pressure, moderate inflammatory control, adequate immune function, stable heart rate | Occasional stress sensitivity, generally stable mood, manageable anxiety levels | Generally regular digestion, occasional discomfort, adequate nutrient absorption |

| Low Vagal Tone | Elevated inflammation, compromised immune function, increased disease risk, poor cardiovascular markers | Heightened anxiety, mood disorders, difficulty managing stress, emotional dysregulation | Irregular bowel movements, poor nutrient absorption, increased gut permeability, digestive disorders |

Low vagal tone correlates with increased risk for various health conditions. These include inflammatory bowel diseases irritable bowel syndrome depression anxiety disorders, and cardiovascular problems. The connection between reduced vagal function and these conditions highlights the importance of supporting vagus nerve health.

Fortunately, vagal tone is not fixed and can be improved through targeted interventions. Several evidence based approaches enhance vagus nerve communication and strengthen vagal function. Deep breathing exercises, particularly those emphasizing slow exhalation directly stimulate the vagus nerve and increase its activity.

Meditation practices activate vagal pathways and improve tone over time. Studies show that regular meditation practitioners demonstrate measurably higher heart rate variability indicating stronger vagal function. Cold exposure, through cold showers or facial immersion in ice water, also stimulates the vagus nerve through the diving reflex.

Dietary interventions play a crucial role in supporting vagal health. Omega-3 fatty acids from fish and algae support nerve membrane function and reduce inflammation. Probiotic-rich foods enhance gut microbiome diversity, which in turn produces metabolites that positively influence vagal signaling. These nutritional approaches create a foundation for improved gut-brain communication through the vagal pathway.

The vagus nerve represents far more than a simple communication cable between organs. It functions as a sophisticated information network that continuously shapes brain function based on gut conditions. This bidirectional pathway, with its predominant flow of information from gut to brain, underscores why digestive health has such profound effects on mental wellness, emotional regulation, and cognitive performance.

4. The Gut Microbiome and Mental Health Connection

The trillions of microorganisms residing in your digestive system hold remarkable power over your mental and emotional states. Scientists have discovered that the gut microbiome and mental health share a complex bidirectional relationship that influences everything from daily mood fluctuations to serious psychiatric disorders.

This connection represents one of the most exciting frontiers in both neuroscience and gastroenterology.

Understanding this relationship opens new possibilities for treating mental health conditions through targeted dietary and lifestyle interventions.

The bacterial communities in your intestines communicate constantly with your brain through multiple pathways. This communication shapes neurotransmitter production immune responses, and stress hormone regulation in ways researchers are only beginning to fully comprehend.

Read more: Gut Microbiome Mental and Physical Health

4.1 Characteristics of a Balanced Gut Microbiome

A healthy gut microbiome contains an astonishing diversity of bacterial species working together in harmony. Most adults harbor between 300 and 1,000 different bacterial species in their digestive tracts. This diversity serves as a key indicator of overall gut health and resilience against disease.

The two dominant bacterial phyla in a balanced microbiome are Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which together account for approximately 90% of gut bacteria.

Within these major groups, beneficial genera like Lactobacillus Bifidobacterium, and Akkermansia perform essential functions. These keystone species help maintain the intestinal barrier produce beneficial metabolites, and regulate immune responses.

The ratio between different bacterial groups matters significantly for health outcomes.

A balanced microbiome maintains appropriate proportions between beneficial and potentially harmful organisms. When beneficial bacteria outnumber problematic ones they prevent pathogenic species from gaining a foothold and causing inflammation or infection.

Microbial diversity declines with age, poor diet antibiotic use, and chronic stress. Maintaining this diversity through proper nutrition and lifestyle choices supports both digestive function and mental wellness. The presence of specific bacterial strains correlates with better emotional regulation and cognitive performance.

4.2 How Gut Bacteria Influence Mood Anxiety and Depression

Gut bacteria influence mental states through several sophisticated mechanisms that directly affect brain chemistry.

One primary pathway involves the production of neuroactive compounds including gamma aminobutyric acid GABA serotonin precursors and short chain fatty acids. These molecules can cross the blood-brain barrier or signal through the vagus nerve to alter brain function.

The relationship between gut microbiome and mental health becomes particularly evident in inflammation regulation. Certain bacterial species produce anti-inflammatory compounds that protect neural tissue from damage. Conversely, an imbalanced microbiome releases pro inflammatory molecules called lipopolysaccharides that trigger systemic inflammation linked to depression and anxiety.

Research consistently shows that individuals with depression exhibit reduced microbial diversity compared to healthy controls. Studies have identified specific bacterial alterations in depressed patients including decreased levels of Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus species. These bacteria normally produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid with anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal HPA axis your body’s central stress response system, receives constant input from gut bacteria. Beneficial microbes help regulate cortisol production and stress reactivity. When microbial balance shifts, the HPA axis can become hyperactive, leading to chronic stress states that contribute to anxiety and mood disorders.

Gut bacteria also influence neurotransmitter availability throughout the body. While the brain produces some neurotransmitters independently bacterial metabolism affects the raw materials and precursors needed for neurotransmitter synthesis. This bacterial influence on neurochemistry provides a direct link between digestive health and emotional well-being.

| Microbiome Characteristic | Balanced State | Imbalanced State Dysbiosis | Mental Health Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Diversity | 300-1,000 different species present | Reduced diversity, fewer than 200 species | Low diversity linked to depression and anxiety |

| Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio | Balanced proportion approximately 1:1 | Skewed ratio favoring one phylum | Altered ratio associated with mood instability |

| Beneficial Bacteria Levels | High levels of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Depleted beneficial species | Reduced stress resilience and emotional regulation |

| Inflammatory Markers | Low lipopolysaccharide production | Elevated inflammatory compounds | Increased risk of depression and cognitive decline |

4.3 Microbial Imbalance and Neuropsychiatric Conditions

Dysbiosis a state of microbial imbalance has emerged as a significant factor in various neuropsychiatric conditions beyond depression and anxiety.

Researchers have identified distinct microbial signatures associated with autism spectrum disorders where affected individuals often show reduced bacterial diversity and elevated levels of certain Clostridium species. These bacterial alterations may contribute to the gastrointestinal symptoms commonly reported in autism.

Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ADHD frequently demonstrate different gut bacterial compositions compared to neurotypical peers.

Studies reveal that these children have lower levels of Bifidobacterium species and altered ratios of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes. The connection between gut microbiome and mental health in ADHD may explain why some children experience symptom improvement with dietary modifications.

Schizophrenia research has uncovered fascinating microbial patterns that distinguish patients from healthy individuals.

People with schizophrenia show increased intestinal permeability and altered bacterial communities that produce different levels of neuroactive metabolites. These findings suggest that gut bacteria may influence the severity of psychotic symptoms through inflammatory and neurotransmitter pathways.

Bipolar disorder also demonstrates connections to microbial imbalance, with patients showing distinct bacterial profiles during manic versus depressive episodes. The cyclical nature of bipolar symptoms may partly reflect fluctuating microbial compositions that affect mood regulation systems. This understanding opens potential therapeutic avenues through targeted probiotic interventions.

The recognition that gut microbiome composition represents a modifiable risk factor for neuropsychiatric conditions has transformed mental health research.

Unlike genetic factors that remain fixed, microbial communities can be reshaped through dietary changes probiotic supplementation, and lifestyle modifications. This modifiability offers hope for new treatment approaches that address mental health from a whole-body perspective rather than focusing exclusively on brain chemistry.

5. Serotonin Production in the Gut and Neurotransmitter Synthesis

Serotonin production in the gut represents one of the most surprising discoveries in modern neuroscience fundamentally reshaping our understanding of mental wellness. The digestive system operates as far more than a food processing organ. It functions as a sophisticated biochemical factory that manufactures the majority of neurotransmitters circulating throughout your body.

This revelation challenges the traditional view that brain chemistry originates exclusively in neural tissue. Instead, the gut plays a primary role in regulating mood, cognition, and emotional states through its neurotransmitter synthesis capabilities. Understanding these mechanisms provides critical insights into how nutrition directly influences mental health.

The Gut as the Body’s Primary Serotonin Factory

The human gastrointestinal tract produces an astonishing 90-95% of the body’s total serotonin supply. Specialized cells called enterochromaffin cells embedded throughout the intestinal lining, manufacture this crucial neurotransmitter. These cells respond to various stimuli including food components, gut bacteria metabolites, and mechanical pressure from digestion.

Enterochromaffin cells release serotonin into the surrounding tissues where it performs multiple functions. This gut derived serotonin regulates intestinal motility controls fluid secretion, and modulates inflammation. The compound also influences appetite, nausea responses, and overall digestive comfort.

However, peripherally produced serotonin faces a significant limitation. The blood-brain barrier prevents these serotonin molecules from directly entering brain tissue. Despite this barrier serotonin production in the gut still profoundly affects mental states through indirect pathways.

The gut communicates serotonin-related signals to the brain through the vagus nerve. Sensory neurons detect serotonin levels in intestinal tissues and transmit this information centrally. The brain then adjusts its own neurotransmitter production based on these peripheral signals creating a feedback loop between digestive and neural systems.

The gut is not only the seat of our physical health, but also a key determinant of our mental and emotional well-being.

Additionally, the precursors needed for brain serotonin synthesis originate from dietary sources processed in the gut. The amino acid tryptophan, which crosses the blood brain barrier serves as the building block for central nervous system serotonin. The gut health and neurotransmitters relationship determines how efficiently these precursors become available for brain use.

Other Critical Neurotransmitters Made in the Digestive Tract

The digestive system manufactures a diverse array of neurotransmitters beyond serotonin. These compounds collectively influence nearly every aspect of brain function and mental health. The gut produces dopamine, GABA norepinephrine, and acetylcholine in significant quantities.

Dopamine, commonly associated with motivation and reward, exists in substantial concentrations throughout the gastrointestinal tract. This neurotransmitter synthesis in the gut helps coordinate digestive movements and regulates immune responses. Gut-derived dopamine also communicates with the brain through neural and hormonal channels.

GABA, the brain’s primary calming neurotransmitter, is produced by both intestinal cells and gut bacteria. This compound reduces neural excitability and promotes relaxation. While gut-produced GABA cannot directly cross into brain tissue, it influences the central nervous system through vagal nerve signaling.

| Neurotransmitter | Primary Function | Gut Production Source | Mental Health Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serotonin | Mood regulation, digestive motility | Enterochromaffin cells | Depression, anxiety, well-being |

| Dopamine | Motivation, reward processing | Intestinal epithelial cells | Pleasure, focus, drive |

| GABA | Neural inhibition, relaxation | Gut bacteria, intestinal cells | Anxiety reduction, calmness |

| Norepinephrine | Alertness, stress response | Enteric neurons | Attention, arousal, stress management |

| Acetylcholine | Memory, learning, muscle control | Enteric nervous system | Cognitive function, memory formation |

Norepinephrine production occurs within enteric neurons that form part of the gut’s independent nervous system. This neurotransmitter influences digestive blood flow and helps coordinate stress responses throughout the body. Its synthesis depends on adequate dietary precursors and enzymatic cofactors.

Acetylcholine, essential for memory and learning, is manufactured by neurons within the enteric nervous system. This compound facilitates communication between nerve cells in the gut wall. It also plays a crucial role in maintaining gut barrier integrity and regulating inflammatory responses.

Gut Bacteria’s Role in Neurotransmitter Manufacturing

The trillions of microorganisms residing in your digestive tract actively participate in neurotransmitter synthesis. Specific bacterial strains produce these compounds directly as part of their metabolic processes. Other microbes provide essential precursors and cofactors that enable human cells to manufacture neurotransmitters.

Several bacterial species demonstrate remarkable neurotransmitter-producing capabilities. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains synthesize GABA from glutamate. Escherichia, Bacillus, and Saccharomyces species produce norepinephrine. Candida, Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Enterococcus strains manufacture serotonin.

The connection between gut health and neurotransmitters extends beyond direct bacterial production. Microbes break down dietary fibers and proteins into short-chain fatty acids and amino acids. These metabolic byproducts serve as building blocks for neurotransmitter synthesis by human intestinal cells.

Key bacterial contributions to neurotransmitter production include:

- Direct synthesis: Bacteria produce finished neurotransmitters through their own enzymatic pathways

- Precursor provision: Microbial metabolism generates amino acids and other compounds needed for neurotransmitter creation

- Cofactor production: Bacteria synthesize B vitamins and other essential cofactors required by neurotransmitter-producing enzymes

- Gene expression regulation: Bacterial metabolites influence human genes that control neurotransmitter synthesis enzymes

Microbial diversity significantly impacts neurotransmitter synthesis efficiency. A balanced microbiome with varied bacterial species produces a broader spectrum of neurotransmitter precursors. Conversely, dysbiosis an imbalanced microbial community can disrupt neurotransmitter production and contribute to mental health challenges.

Antibiotics, diet changes, and stress can alter the gut microbiome composition. These disruptions affect bacterial neurotransmitter synthesis capabilities. Research shows that restoring microbial balance through targeted probiotic supplementation can normalize neurotransmitter levels and improve mood symptoms.

The Impact of Neurotransmitter Levels on Brain Function

Gut-derived neurotransmitter systems exert profound influence over cognitive performance, emotional regulation, and mental health outcomes. While these peripherally produced compounds cannot directly enter the brain they communicate through multiple indirect pathways. This communication shapes brain chemistry and neurological function in measurable ways.

The vagus nerve serves as the primary information highway transmitting gut neurotransmitter signals to the brain. Sensory neurons within intestinal tissues detect local neurotransmitter concentrations. These neurons send signals to brain regions controlling mood stress responses and decision making.

Altered serotonin production in the gut correlates with depression and anxiety disorders. Studies demonstrate that individuals with irritable bowel syndrome a condition marked by disrupted gut serotonin signaling experience significantly higher rates of anxiety and depression.

Correcting peripheral serotonin dysfunction through dietary interventions often improves both digestive and mental health symptoms.

Dopamine synthesis in the digestive tract influences motivation and reward processing. Reduced gut dopamine production associates with diminished drive focus difficulties, and anhedonia. Supporting healthy dopamine levels through gut health and neurotransmitters optimization can enhance cognitive performance and emotional resilience.

GABA production by gut bacteria directly impacts anxiety levels and stress responses. Research indicates that probiotic strains producing GABA reduce anxiety like behaviors in both animal and human studies. This effect occurs through vagal nerve communication and systemic inflammatory modulation.

The brain monitors peripheral neurotransmitter status and adjusts central production accordingly. Low gut-derived neurotransmitter signals prompt the brain to conserve its own neurotransmitter supplies. This compensatory mechanism can lead to reduced neural signaling efficiency and compromised mental function over time.

Neurotransmitter synthesis depends heavily on nutrient availability. Deficiencies in key vitamins, minerals, and amino acids impair both gut and brain neurotransmitter production. Vitamin B6, folate, magnesium, zinc, and iron serve as essential cofactors for neurotransmitter producing enzymes.

The tryptophan-to-serotonin conversion pathway illustrates this nutrient dependency. Dietary tryptophan absorbed in the gut must compete with other amino acids for transport across the blood-brain barrier. High protein meals increase competing amino acids potentially reducing tryptophan availability for brain serotonin synthesis.

Inflammation originating in the gut disrupts neurotransmitter metabolism throughout the body. Inflammatory cytokines activate enzymes that divert tryptophan away from serotonin production. This mechanism partially explains why gut inflammation frequently accompanies mood disorders and cognitive decline.

Understanding these connections establishes the biochemical foundation for nutritional psychiatry interventions. Optimizing gut health through targeted dietary strategies can enhance neurotransmitter synthesis and improve mental wellness. This approach offers a practical side effect-free method for supporting brain function through digestive system optimization.

6. The Gut Brain Connection How it Works and The Role of Nutrition

Food serves as more than fuel for the body it acts as a biological information system that directly influences brain function and emotional well-being.

Every meal you consume sends chemical signals throughout your digestive system impacting the trillions of bacteria in your gut the production of neurotransmitters, and ultimately the way your brain processes emotions and thoughts. The emerging field of nutritional psychiatry examines these connections revealing that dietary choices represent a powerful modifiable factor in mental health treatment and prevention.

Understanding how specific nutrients, foods, and eating patterns affect the gut-brain axis opens new possibilities for addressing conditions like depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline. This section explores the mechanisms behind these effects and identifies practical nutritional strategies that support optimal mental wellness.

6.1 Nutritional Psychiatry and the Food-Mood Relationship

Nutritional psychiatry represents a paradigm shift in how we view mental health treatment. This field examines how dietary patterns individual nutrients, and gut microbiome health influence psychological well being. Traditional psychiatry focused primarily on neurotransmitter imbalances and psychological factors but researchers now recognize that what happens in the gut profoundly affects what happens in the brain.

Studies consistently demonstrate strong connections between diet quality and mental health outcomes.

Populations consuming traditional whole food diets show significantly lower rates of depression and anxiety compared to those eating processed Western-style diets. One landmark study found that individuals with the highest diet quality scores had a 25-35% lower risk of developing depression compared to those with the poorest diets.

The food-mood relationship operates through multiple channels. When you eat nutrient-dense foods, you provide your body with the raw materials needed to produce mood regulating neurotransmitters. Conversely diets high in refined sugars and processed foods promote inflammation and oxidative stress both of which damage brain cells and impair mental function.

The timing of dietary changes matters for mental health improvements.

Research shows that individuals who adopt healthier eating patterns experience measurable improvements in mood symptoms within just three weeks. These rapid changes suggest that nutritional interventions can complement traditional treatments like therapy and medication offering a holistic approach to mental wellness.

Read more: 10 Healthy Habits to Boost Beauty and Wellness

6.2 Mechanisms Through Which Diet Influences Brain Health

Diet affects brain function through several interconnected biological pathways.

Understanding these mechanisms reveals why nutrition for brain health extends far beyond simply providing energy. The first pathway involves neurotransmitter production as amino acids from dietary protein serve as building blocks for serotonin dopamine, and other chemical messengers that regulate mood and cognition.

The second mechanism centers on inflammation control. Certain foods trigger inflammatory responses throughout the body including the brain. Chronic low grade inflammation damages neurons disrupts neurotransmitter balance, and contributes to conditions like depression and cognitive decline. Anti-inflammatory foods help protect brain tissue and support optimal neural function.

Oxidative stress represents another critical pathway. Your brain uses tremendous amounts of oxygen and energy, generating reactive molecules called free radicals as byproducts. Without adequate antioxidants from food, these free radicals damage cellular structures and accelerate brain aging.

Blood sugar regulation directly impacts mental states and cognitive performance. Foods that cause rapid spikes and crashes in glucose levels create corresponding fluctuations in energy, focus, and emotional stability. Steady blood sugar supports consistent neurotransmitter production and energy supply to brain cells.

The gut microbiome composition shifts in response to dietary patterns, and these microbial changes influence brain function through the production of metabolites, neurotransmitters, and inflammatory compounds. A diet rich in fiber and fermented foods promotes beneficial bacteria that support mental health, while processed foods favor harmful species that may contribute to depression and anxiety.

Blood-brain barrier integrity depends on proper nutrition. This protective barrier prevents toxins and pathogens from entering brain tissue. Certain nutrients strengthen this barrier, while inflammatory foods can compromise it, allowing harmful substances to reach the brain.

6.3 Key Nutrients Essential for Gut Brain Axis Function

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA and EPA form essential components of brain cell membranes and support neurotransmitter receptor function. These fats reduce inflammation throughout the nervous system and promote the growth of new brain cells.

Studies link adequate omega-3 intake with lower rates of depression and better cognitive performance. Rich food sources include fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, and sardines, as well as walnuts, flaxseeds, and chia seeds.

B vitamins serve as critical cofactors in neurotransmitter synthesis and energy metabolism. Vitamin B6 helps convert tryptophan into serotonin, while B12 and folate support the methylation processes essential for brain function. Deficiencies in these vitamins strongly correlate with increased depression risk. You can find B vitamins in leafy greens legumes whole grains eggs, and animal proteins.

Vitamin D functions as both a hormone and a neuroprotective agent. It regulates genes involved in brain development and function, and low levels associate with increased risks of depression, seasonal affective disorder, and cognitive decline. While sunlight exposure helps your body produce vitamin D, dietary sources include fatty fish fortified dairy products, and egg yolks.

Magnesium participates in over 300 enzymatic reactions, including those that regulate stress response and neurotransmitter activity. This mineral helps calm nervous system activity and supports healthy sleep patterns.

Magnesium deficiency is common and contributes to anxiety, irritability, and poor stress resilience. Dark leafy greens, nuts, seeds, legumes, and whole grains provide excellent magnesium sources.

Zinc supports neurotransmitter production and modulates brain signaling. It also plays vital roles in immune function and inflammation control. Low zinc levels link to depression and impaired cognitive function. Oysters contain the highest zinc concentrations but beef, pumpkin seeds chickpeas, and cashews also provide significant amounts.

Tryptophan and other amino acids serve as precursors for neurotransmitter synthesis. Tryptophan specifically converts to serotonin, affecting mood sleep, and appetite regulation. Complete protein sources like poultry fish eggs, and dairy provide all essential amino acids, while plant sources like quinoa, soy products, and combinations of grains with legumes also deliver these building blocks.

Polyphenols act as powerful antioxidants that protect brain cells from oxidative damage while reducing inflammation. These plant compounds also support beneficial gut bacteria that produce mood-regulating metabolites. Berries, dark chocolate green tea, extra virgin olive oil and colorful vegetables contain high polyphenol concentrations.

Dietary fiber feeds beneficial gut bacteria, which produce short-chain fatty acids that influence brain function and reduce inflammation. Fiber also stabilizes blood sugar and supports the gut barrier. Whole grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, and seeds all contribute valuable fiber to your diet.

6.4 Dietary Patterns That Support Mental Wellness

Individual nutrients matter, but overall dietary patterns show even stronger associations with mental health outcomes. The Mediterranean diet has received extensive research attention for its mental health benefits. This eating pattern emphasizes vegetables fruits whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil, and fish, while limiting red meat and processed foods.

Multiple studies demonstrate that people following Mediterranean-style eating patterns experience significantly lower rates of depression and cognitive decline.

One intervention trial showed that individuals with depression who adopted this diet experienced substantial mood improvements, with many achieving remission of their symptoms. The diet works through multiple mechanisms providing anti-inflammatory nutrients, supporting diverse gut microbiota delivering steady energy through complex carbohydrates, and supplying abundant antioxidants.

The traditional Japanese diet represents another pattern associated with excellent mental health outcomes. This approach features fish, seaweed, fermented soy products, vegetables, and green tea. These foods provide omega-3 fatty acids, iodine for thyroid function, probiotics, and polyphenols that collectively support brain health.

Whole-food, plant rich eating patterns consistently correlate with better mental wellness regardless of specific cultural traditions. These diets share common features high fiber content that nourishes beneficial gut bacteria abundant antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, steady blood sugar from complex carbohydrates, and minimal processed ingredients that could trigger inflammation.

The key principle underlying all beneficial dietary patterns is food quality over calorie counting. Focus on nutrient density choosing foods that deliver maximum vitamins, minerals, and beneficial compounds relative to their calorie content. This approach naturally reduces intake of processed foods high in refined sugars, unhealthy fats, and artificial additives that compromise both gut and brain health.

Practical implementation of these patterns doesn’t require perfect adherence. Research suggests that even moderate improvements in diet quality produce measurable mental health benefits. Start by adding more vegetables choosing whole grains over refined options, including fatty fish twice weekly, and incorporating fermented foods like yogurt or sauerkraut regularly.

The social and cultural aspects of eating also contribute to mental wellness. Traditional diets typically involve shared meals, food preparation rituals, and seasonal eating patterns that support psychological well-being beyond the nutrients themselves. Nutritional psychiatry recognizes these broader dimensions of how we eat, not just what we eat.

| Nutrient Category | Primary Brain Benefits | Top Food Sources | Daily Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Reduces inflammation, supports neuron structure, enhances mood regulation | Fatty fish, walnuts, flaxseeds, chia seeds | 250-500mg combined EPA/DHA |

| B Vitamins B6, B12, Folate | Neurotransmitter synthesis, methylation processes, energy metabolism | Leafy greens, legumes, eggs, fish, poultry | B6: 1.3-1.7mg, B12: 2.4mcg, Folate: 400mcg |

| Polyphenols | Antioxidant protection, inflammation reduction, microbiome support | Berries, dark chocolate, olive oil, green tea | Multiple servings of colorful plant foods daily |

| Dietary Fiber | Feeds beneficial gut bacteria, stabilizes blood sugar, supports gut barrier | Whole grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts | 25-35 grams per day |

The integration of nutritional approaches with conventional mental health treatments represents the future of psychiatric care. Rather than viewing medication therapy, and nutrition as separate interventions nutrition for brain health works synergistically with other treatments to optimize outcomes.

Many mental health professionals now incorporate dietary assessments and recommendations into their treatment plans, recognizing that addressing nutritional deficiencies and improving diet quality can enhance the effectiveness of other interventions.

Individual responses to dietary changes vary based on genetics, existing microbiome composition baseline nutritional status, and other factors.

Some people notice rapid improvements in mood and energy within days of dietary modifications, while others require several weeks to experience significant changes. This variability highlights the importance of personalized approaches that consider individual circumstances and needs.

The preventive potential of optimal nutrition deserves emphasis. While much research examines dietary interventions for existing mental health conditions evidence suggests that maintaining high diet quality throughout life reduces the risk of developing depression anxiety, and cognitive decline. Investing in nutritional health early creates a foundation for lifelong mental wellness.

7. Diet Impact on Mood and Cognitive Performance

Your dietary choices influence brain function more powerfully than most people realize, affecting everything from daily mood to long term cognitive health. The diet impact on mood operates through multiple biological pathways including neurotransmitter synthesis inflammation levels blood sugar stability, and gut microbiome composition.

Understanding these connections empowers you to make food choices that support both mental clarity and emotional balance.

Research demonstrates that what you eat today directly affects how you think and feel tomorrow. The nutrients from your meals provide the raw materials your brain needs to manufacture mood-regulating chemicals. They also determine whether your gut environment promotes mental wellness or contributes to cognitive difficulties.

7.1 Brain-Boosting Foods and Their Mechanisms

Certain foods have demonstrated remarkable abilities to enhance cognitive performance and stabilize mood through specific biological mechanisms. These brain-boosting foods work by supporting neurotransmitter production, reducing oxidative stress, and nourishing beneficial gut bacteria.

Fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, and sardines contain high concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids that form essential components of neuronal membranes. These fats improve communication between brain cells and reduce inflammation that can impair cognitive function.

Regular consumption has been linked to better memory, faster processing speed, and reduced risk of depression.

Berries, particularly blueberries and strawberries, deliver powerful antioxidants called flavonoids that cross the blood-brain barrier. These compounds protect neurons from oxidative damage, improve blood flow to the brain, and may delay age related cognitive decline. Studies show that people who eat berries regularly perform better on memory tests.

Leafy green vegetables like spinach, kale, and Swiss chard provide folate, magnesium, and vitamin K that support brain health. Folate plays a critical role in neurotransmitter synthesis, while magnesium regulates stress responses and promotes restful sleep. These nutrients work together to maintain cognitive function and emotional stability.

Fermented foods including yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi introduce beneficial bacteria directly to your gut microbiome. These probiotics produce neurotransmitter precursors and short-chain fatty acids that reduce inflammation throughout the body. The gut bacteria from fermented foods communicate with the brain through the vagus nerve, influencing mood and anxiety levels.

Nuts and seeds offer a combination of healthy fats, minerals, and plant compounds that protect brain tissue. Walnuts contain alpha-linolenic acid that converts to omega-3s in the body. Pumpkin seeds provide zinc essential for neurotransmitter function while almonds deliver vitamin E that protects against cognitive decline.

Dark chocolate with at least 70% cacao contains flavonoids and small amounts of caffeine that enhance focus and mood. The compounds in dark chocolate increase blood flow to the brain and stimulate the production of endorphins. Moderate consumption may improve cognitive performance during demanding mental tasks.

7.2 Inflammatory Foods and Cognition Decline

While some foods support brain health, others actively damage cognitive function through inflammatory pathways. The relationship between inflammatory foods and cognition has become increasingly clear as research reveals how dietary choices trigger systemic inflammation that reaches the brain.

Ultra-processed foods represent one of the most significant dietary threats to mental performance. These products contain artificial additives preservatives, and flavor enhancers that disrupt gut barrier integrity. When the gut lining becomes permeable, bacterial toxins enter the bloodstream and trigger widespread inflammation that affects brain tissue.

Refined sugars cause rapid blood glucose spikes followed by crashes that impair concentration and mood stability. High sugar intake also promotes the growth of harmful gut bacteria that produce inflammatory compounds. Over time, excessive sugar consumption has been linked to increased risk of depression and accelerated cognitive aging.

Trans fats found in many fried foods and baked goods damage cell membranes throughout the body, including neurons. These artificial fats increase inflammation, reduce blood flow to the brain, and interfere with neurotransmitter signaling. Studies consistently show that people who consume high amounts of trans fats experience faster cognitive decline.

Excessive omega-6 fatty acids create an inflammatory environment when consumed in disproportionate amounts compared to omega-3s. The typical Western diet contains 15-20 times more omega-6 than omega-3 fatty acids. This imbalance promotes the production of pro-inflammatory molecules that can damage brain cells and impair mental function.

The negative effects of these foods extend beyond direct brain damage. They also reduce gut microbiome diversity, decrease beneficial bacteria populations, and compromise the production of mood-regulating neurotransmitters. This creates a cycle where poor dietary choices lead to gut dysfunction, which further worsens mental health.

7.3 The Role of Blood Sugar Regulation in Mood Stability

Blood sugar fluctuations exert powerful effects on emotional states and cognitive performance that many people fail to recognize. When glucose levels swing dramatically throughout the day, the brain experiences periods of fuel shortage that trigger mood changes and mental fog.

Blood sugar regulation begins with understanding the glycemic impact of different foods. High-glycemic foods cause rapid glucose spikes that prompt insulin surges. When insulin drives blood sugar down too quickly, you may experience irritability, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, and sudden fatigue.

These crashes affect neurotransmitter balance in the brain. Low blood sugar reduces serotonin production which directly impacts mood and impulse control. It also activates stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline as the body attempts to raise glucose levels. This hormonal response can feel like anxiety or panic.

Maintaining stable blood sugar requires strategic meal composition and timing. Each meal should combine protein, healthy fats, and fiber-rich carbohydrates. This combination slows glucose absorption and provides steady energy to the brain over several hours.

- Include protein at every meal to slow carbohydrate digestion and promote satiety

- Choose whole grains over refined carbohydrates to benefit from fiber content

- Add healthy fats like avocado, olive oil, or nuts to further stabilize glucose release

- Eat regular meals every 3-4 hours to prevent dramatic blood sugar drops

- Avoid consuming carbohydrates alone, especially sugary foods without protein or fat

Fiber intake plays an especially important role in glycemic control. Soluble fiber forms a gel in the digestive tract that slows sugar absorption. This prevents the rapid glucose spikes that lead to mood instability. Aim for at least 25-30 grams of fiber daily from vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains.

Proper meal timing supports both blood sugar stability and circadian rhythm regulation. Eating breakfast within an hour of waking helps establish healthy glucose patterns for the day. Avoiding large meals close to bedtime prevents nighttime blood sugar fluctuations that can disrupt sleep quality.

7.4 Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Brain Health

Omega-3 fatty acids stand out as perhaps the most extensively researched nutrients for brain health and mental wellness. These essential fats cannot be produced by the body and must come from dietary sources. The two most important forms for brain function are EPA eicosapentaenoic acid and DHA docosahexaenoic acid.

DHA comprises approximately 40% of the polyunsaturated fatty acids in brain tissue and 60% of those in the retina. It forms a crucial structural component of neuronal cell membranes, influencing membrane fluidity and the function of embedded proteins. This structural role affects how efficiently neurons communicate with each other.

EPA primarily functions as an anti-inflammatory agent throughout the body and brain. It competes with omega-6 fatty acids for the same enzymes, reducing the production of inflammatory molecules. This anti-inflammatory action protects neurons from damage and supports optimal cognitive function.

Research demonstrates that omega-3 fatty acids influence neurotransmitter receptor density and sensitivity. They enhance serotonin and dopamine signaling by improving receptor function in neuronal membranes. This effect helps explain why omega-3 supplementation shows benefits for depression and other mood disorders.

| Omega-3 Source | EPA Content per 3 oz | DHA Content per 3 oz | Additional Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Salmon | 400-900 mg | 500-1,200 mg | High in vitamin D and selenium |

| Sardines | 400-500 mg | 500-700 mg | Calcium from edible bones |

| Mackerel | 400-700 mg | 600-1,000 mg | Rich in vitamin B12 |

| Flaxseeds ground | Converts to EPA | Limited conversion | High fiber and lignans |

| Walnuts | Converts to EPA | Limited conversion | Antioxidants and magnesium |

Clinical trials have demonstrated significant benefits of omega-3 supplementation for various mental health conditions. Meta-analyses show that EPA-rich supplements reduce symptoms of major depression comparably to some pharmaceutical interventions. Doses of 1-2 grams of EPA daily appear most effective for mood disorders.

Omega-3s also support cognitive performance across the lifespan. In children and adolescents, adequate intake supports brain development and may improve attention and learning. In adults, omega-3 consumption correlates with better memory, processing speed, and executive function. Older adults with higher omega-3 levels show slower rates of cognitive decline.

The anti-inflammatory properties of these fatty acids extend to gut health as well. Omega-3s help maintain gut barrier integrity, reduce intestinal inflammation, and support a balanced microbiome. This creates a positive feedback loop where improved gut health further enhances the diet impact on mood through the gut-brain axis.

For optimal brain health, aim to consume fatty fish at least twice weekly or consider a high quality fish oil supplement providing 1-2 grams of combined EPA and DHA daily. Plant sources like flaxseeds chia seeds, and walnuts provide ALA alpha-linolenic acid which converts to EPA and DHA at limited rates of 5-10%. Vegetarians and vegans may benefit from algae-based omega-3 supplements that provide preformed EPA and DHA.

The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in your diet significantly impacts inflammation levels and brain function. Reducing intake of omega-6-rich vegetable oils while increasing omega-3 consumption helps restore balance. This dietary shift reduces inflammatory foods and cognition problems while supporting mental clarity and emotional resilience.

8. Probiotics and Brain Function: The Psychobiotic Revolution

The psychobiotic revolution demonstrates that what we feed our gut microbiome can reshape our emotional landscape. This emerging field bridges nutrition science and mental health treatment in ways previously unimaginable. Research now confirms that specific living organisms can influence everything from daily mood to clinical anxiety disorders.

The connection between probiotics and brain function represents one of the most exciting frontiers in neuroscience. Scientists have identified particular bacterial strains that communicate directly with the central nervous system. These specialized microorganisms offer a natural approach to supporting cognitive health and emotional balance.

Understanding how these beneficial bacteria work requires exploring their multiple mechanisms of action. The evidence supporting their use continues to grow with each new clinical study. This section examines the science behind psychobiotics and their practical applications for mental wellness.

8.1 What Are Psychobiotics and How Do They Work

Psychobiotics are live microorganisms that produce mental health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts. Unlike general probiotics that focus on digestive health, these specialized strains target the gut-brain axis specifically. They represent a distinct category within the broader probiotic family.

These remarkable bacteria operate through multiple pathways simultaneously. Their primary mechanism involves producing neurotransmitters and their chemical precursors directly in the gut. Beneficial bacteria manufacture compounds like GABA serotonin, and dopamine that influence brain chemistry.

The stress response system receives significant modulation from psychobiotics. These organisms help regulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which controls cortisol production. Lower stress hormone levels translate to improved resilience against daily pressures and anxiety triggers.

Inflammation reduction represents another critical mechanism through which psychobiotics work. They strengthen the intestinal barrier to prevent harmful substances from entering the bloodstream. This protective action prevents systemic inflammation that can damage brain tissue and impair mental function.

Short-chain fatty acids produced by psychobiotics carry neuroactive properties. Compounds like butyrate cross the blood-brain barrier and support neuronal health directly. These metabolites also reduce inflammation and provide energy to brain cells.

Psychobiotics represent a paradigm shift in how we conceptualize mental health treatment, offering a biological intervention that works with the body’s natural systems rather than against them.

Direct communication with the nervous system occurs through vagal pathways. The bacteria send signals that travel along the vagus nerve to the brain. This bidirectional communication allows gut microbiota to influence emotional processing and cognitive function in real-time.

8.2 Evidence for Probiotics in Mood Regulation and Anxiety Reduction

Clinical research on probiotics for mood regulation has produced compelling results across multiple studies. Randomized controlled trials demonstrate measurable improvements in psychological symptoms. The evidence base continues expanding as researchers conduct increasingly sophisticated investigations.

Depression symptoms show significant reduction in participants taking specific probiotic formulations. Studies lasting eight to twelve weeks reveal decreased scores on standardized depression rating scales. Participants report improvements in energy levels, motivation, and overall emotional well-being.

Anxiety reduction appears consistently across various clinical trials. Individuals consuming targeted probiotic strains experience lower anxiety scores compared to placebo groups. These benefits extend to both general anxiety and stress-related symptoms.

Stress hormone measurements provide objective evidence of psychobiotic effectiveness. Cortisol levels decrease in study participants taking probiotics for mood regulation. Salivary cortisol testing shows reduced stress response to challenging situations and improved recovery patterns.

Cognitive function and memory enhancement emerge as additional benefits in research findings. Study participants demonstrate improved performance on attention tasks and working memory tests. These cognitive improvements correlate with changes in gut microbiome composition.

Emotional processing becomes more balanced with regular psychobiotic supplementation. Brain imaging studies reveal altered activity in regions responsible for emotional regulation. Participants show reduced reactivity to negative stimuli and improved emotional resilience.

The reduction of rumination and negative thought patterns represents a particularly valuable benefit. Individuals report fewer intrusive negative thoughts and decreased tendency toward worry. This shift in cognitive patterns contributes significantly to overall mental health improvement.

Current research limitations warrant acknowledgment alongside these promising findings. Questions remain about optimal dosing strategies and treatment duration for different conditions. Individual variability in response highlights the need for personalized approaches to psychobiotic therapy.

8.3 Prebiotic Fiber Foods That Nourish Beneficial Bacteria

Prebiotic fibers serve as essential fuel for the beneficial bacteria residing in your gut. These non-digestible food components reach the colon intact where microorganisms ferment them. The resulting metabolic activity supports a thriving gut microbiome ecosystem.

Understanding prebiotics proves equally important as knowing about probiotics themselves. You cannot establish lasting gut health improvements without proper nourishment for beneficial bacteria. The two work synergistically to create optimal conditions for mental wellness.

Numerous whole foods provide abundant prebiotic fiber to support psychobiotic activity. Incorporating these ingredients into daily meals ensures your gut bacteria receive consistent nourishment. The diversity of prebiotic sources allows for varied and enjoyable dietary patterns.

- Onions and garlic: Rich in inulin and fructooligosaccharides that selectively feed beneficial bacteria

- Leeks and asparagus: Contain high concentrations of prebiotic compounds that support Bifidobacteria growth

- Bananas: Provide resistant starch and pectin that nourish diverse microbial populations

- Oats and barley: Deliver beta-glucan fibers that promote beneficial bacterial proliferation

- Flaxseeds and chia seeds: Supply soluble fiber and omega-3 fatty acids for comprehensive gut support

- Jerusalem artichokes: Offer exceptional inulin content for robust prebiotic effects

The fermentation of prebiotic fiber produces short-chain fatty acids with brain benefits. Butyrate, propionate, and acetate all contribute to neurological health. These compounds reduce inflammation, strengthen the gut barrier, and support neurotransmitter production.

Combining prebiotic foods with probiotic sources creates a synbiotic effect. This partnership enhances the survival and colonization of beneficial bacteria. Your mental health benefits increase when both elements work together harmoniously.

Gradual introduction of prebiotic foods prevents digestive discomfort during adaptation. Start with smaller portions and slowly increase intake over several weeks. This approach allows your gut microbiome to adjust without causing bloating or gas.

8.4 Specific Probiotic Strains with Mental Health Benefits

Scientific research has identified particular probiotic strains with documented effects on brain function and mood. Not all probiotics offer equal mental health benefits, making strain specificity crucial. Understanding which bacteria provide psychobiotic effects helps guide supplement selection and dietary choices.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus stands out for its anxietyreducing properties demonstrated in multiple studies. This strain shows particular effectiveness in lowering stress-induced cortisol levels. Research participants taking this bacterium report decreased anxiety symptoms and improved stress resilience.

Bifidobacterium longum demonstrates significant benefits for depression and cognitive function. Clinical trials reveal improvements in mood scores and reduced psychological distress. This strain also supports memory formation and learning capacity through its neurochemical effects.

Lactobacillus helveticus combined with Bifidobacterium longum creates a powerful psychobiotic formula. This pairing shows effectiveness for both anxiety and depression in clinical settings. The synergistic action of these strains produces stronger results than either bacterium alone.

| Probiotic Strain | Primary Mental Health Benefit | Typical Daily Dosage | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Anxiety reduction and stress management | 1-10 billion CFU | Multiple RCTs showing reduced cortisol |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Depression relief and cognitive enhancement | 1-10 billion CFU | Clinical trials with mood improvement |

| Lactobacillus helveticus | Mood stabilization and emotional balance | 3-9 billion CFU | Studies demonstrating reduced distress |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Cognitive function and memory support | 1-10 billion CFU | Research showing learning enhancement |

Multi-strain formulations often provide broader mental health support than single-strain products. Combining complementary bacteria creates diverse benefits across mood, cognition, and stress response. Look for supplements containing at least three to five documented psychobiotic strains.

Quality considerations matter significantly when selecting probiotic supplements for mental health benefits. Choose products with guaranteed potency through expiration date, not just at manufacture. Refrigerated options typically maintain higher viability though some shelf-stable formulations use protective technologies.

The future of mental health treatment lies not in replacing traditional therapies but in augmenting them with evidence based interventions that address the biological foundations of mood and cognition.

Fermented foods provide natural sources of beneficial bacteria alongside their prebiotic content. Yogurt with live active cultures delivers multiple Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains. Kefir offers even greater bacterial diversity with 30 to 50 different microbial species.

Sauerkraut and kimchi supply probiotics along with vitamin C and other nutrients that support brain health. The fermentation process enhances nutrient bioavailability while creating beneficial organic acids. Regular consumption of these foods supports sustained gut microbiome improvements.

Kombucha provides probiotics in a refreshing beverage format that many find appealing. This fermented tea contains beneficial yeasts and bacteria that support digestive and mental health. Choose varieties with minimal added sugar to maximize health benefits.

Incorporating both supplemental and food-based probiotics creates comprehensive support for the gut-brain axis. This dual approach ensures consistent bacterial intake while providing dietary variety. The combination enhances colonization success and long-term microbiome improvements that translate to better mental wellness.

9. Stress Impact on Digestion and Anti-Inflammatory Diet Benefits

When stress becomes a constant companion, your digestive system pays a steep price that extends far beyond occasional stomach discomfort. The connection between psychological pressure and gut health operates through complex biological mechanisms that affect every aspect of digestive function.